When British politicians speak about Brexit and its penalties, they have an inclination to undertake rictus grins and guarantee us that, by some miracle as but unexplained, every little thing goes to be OK. The Labour chief Keir Starmer, who just a few years in the past was a passionate advocate of a second referendum on our exit from the EU, now has a five-point plan to “make Brexit work”. In the meantime, because the Tory leadership contest grinds on, each the candidates are at pains to assert that life exterior the EU goes splendidly properly, or quickly will do.

Irrespective of that leaving the EU has twisted up companies in form-filling, charges and a brand new world of unbelievable complexity: Rishi Sunak says he desires to “go additional and quicker in utilizing the freedoms Brexit has given us to chop the mass of EU laws and paperwork holding again our progress”. Liz Truss sounds much more zealous: she now desires to scrap all of the laws in UK legislation which are there because the legacy of our time within the EU by the tip of subsequent yr, to “take advantage of our newfound freedoms exterior the EU”.

Six years in the past, Truss – not like Sunak – enthusiastically campaigned for stay, however she is now very happy to eat her phrases. “I used to be improper and I’m ready to confess I used to be improper,” she lately advised the BBC. “A few of the portents of doom didn’t occur and as an alternative we’ve really unleashed new alternatives.”

That “some” is a really telling use of language. The peace course of in Northern Eire and the power-sharing association it created – maybe the best achievement of post-Thatcher British politics – have been severely destabilised. The UK is an more and more lonely, typically downright odd presence on the world stage. Most of Europe, certainly, appears to suppose we’ve gone collectively mad.

After which there’s the influence on our on a regular basis lives. Within the face of Westminster’s combination of silence and compelled optimism, Brexit is having a measurably dire impact on nearly all of us. A latest survey performed by the opinion pollsters Ipsos confirmed that the proportion of Britons who suppose the UK’s exit from the EU has made their every day life worse has gone up from 30% in June 2021 to 45% now, a determine that features just below 1 / 4 of people that voted depart. Amid the aftershocks of our nationwide lockdowns, these mounting issues have gotten ever extra apparent. And so, by the use of filling the informational hole left by our legislators – and, certainly, many of the media – this unusual, baking-hot summer season looks like time to set out simply a few of Brexit’s apparently limitless downsides. Beginning with …

Britain in 2022 is a rustic of lengthy waits, spiralling queues and that omnipresent feeling that not almost sufficient individuals are being employed to maintain every little thing operating. Our scarcity of employees extends from pubs to hospitals: one of the worrying examples is what is occurring to grownup social care, which is already reeling from the pandemic.

To state the blindingly apparent, regardless of its self-evident significance, care is a low-paid, low-status line of labor, which tends to have excessive charges of employees turnover. Because the variety of older individuals will increase, so does the prevalence of typically persistent well being situations, which implies we’d like an increasing number of care employees. However Brexit has pulled an already struggling a part of our social material into even larger disaster.

“It’s been devastating,” says Nadra Ahmed, the chair of the Nationwide Care Affiliation, which represents small and medium-sized care suppliers. “It’s made an already declining state of affairs, a lot, a lot worse. We’ve misplaced quite a lot of our European colleagues. They determined they now not wished to remain. They felt undesirable, unsafe, undervalued.”

Two years in the past, she tells me, 5.2% of these beginning new jobs in grownup social care had been international nationals; now, that determine is lower than 2%. Below strain from care employers, the federal government lately relaxed stringent restrictions on visas for care employees, however staffing issues proceed to mount.

To make issues even worse, Brexit-related labour shortages in different fields of labor are pulling individuals away from care in growing numbers, with apparent penalties. In Might 2021, the emptiness price in grownup social care was 5.9%. In April this yr, it reached 10%.

For individuals who want residential care, the results could be grim. “Numerous suppliers have stopped taking individuals from hospitals who’re high-need, as a result of they don’t have the employees to manage,” says Ahmed. “Or they’ve closed a share of the beds of their providers. Should you’ve bought a 30-bed service, you may deliver it all the way down to 25 beds, so that you’ve bought the appropriate ratio of employees.”

And what does that imply for individuals who want care?

“Properly, they’re typically caught in hospital, which is why you hear about all points within the NHS with that terrible time period ‘bedblocking’. That’s individuals sitting in NHS hospitals who’re medically match for discharge, however they will’t be positioned wherever as a result of no service can ship the care.”

2

What Brexit means for British food-growers

Britain is seemingly in need of meals, starvation is an more and more seen downside, and empty cabinets in supermarkets are actually an ingrained a part of on a regular basis life – however we’re additionally throwing away tonnes of produce.

Ali Capper is the proprietor of a farm in Worcestershire that grows apples and hops. When harvests peak between late August and mid-October, she wants about 70 non permanent workers. “We’re fairly small-to-medium in that respect,” she says. “There are gentle fruit growers who’ll make use of 1,000 to 1,500 for the summer season, and vegetable growers who want extra like 2,500 to three,000.”

Since 2017, getting sufficient employees has been an annual headache. “Should you haven’t bought labour, you possibly can’t harvest your crop, and also you don’t have a enterprise,” she says. “It’s so simple as that. And we’ve had two years once we’ve needed to stroll previous crops: that’s how we describe it. You must begin prioritising. You permit the much less good, or the marginal, or the second-pick: the crop that may not get you the best return.”

What quantity of her produce has been thrown away? “I’m not going to crystal-ball this season,” she says. “However in earlier seasons, we’ve in all probability left behind as much as 25%. That’s actually painful.” The place does it depart the enterprise? “Properly, I might say that in contemporary produce, many companies are questioning their sustainability.”

For the reason that referendum, the make-up of her workforce has drastically modified. It was break up between individuals from Poland, Romania and Bulgaria, lots of whom would come again three or 4 seasons operating, and turn out to be knowledgeable pickers. Now, employees come from such nations as Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Ukraine and Russia – and convulsive latest occasions within the latter two nations have meant extra individuals solely coming for a single interval, which has led to a drop in productiveness.

There’s additionally, Capper says, a rising situation with a number of the export firms she offers with, as evidenced by a Worcestershire-based hops service provider she is aware of who’s about to arrange a brand new warehouse in Poland. “Hops is a world enterprise,” she says. “If he brings hops in from Australia or America, and he desires to bundle them up with hops from the UK and ship every little thing into Europe, he’s paying double responsibility. The one approach of avoiding that’s instantly importing hops into Europe. So we’re going to see retailers with a deal with Europe moderately than right here. And which means UK hops will get forgotten.”

3

Brexit can also be horrible for meals imports

Earlier than Brexit occurred, Truss famously alerted the Conservative get together convention to the truth that the UK imported two-thirds of its cheese – which was, she half yelled, “a shame”. She is, due to this fact, presumably ecstatic concerning the seemingly limitless snags that now face British patrons of European dairy merchandise – and, for that matter, numerous different EU foodstuffs apart from. Meals importers face most of the identical bureaucratic nightmares as exporters (within the phrases of Speciality Meals journal, “with Brexit now formally in full power, cheesemongers throughout the UK are fighting prices and provider points relating to importing European cheeses”), which is likely one of the the reason why the refrigerated aisles of many British supermarkets are sometimes so sparsely stocked. Observe additionally: the British authorities was as a consequence of introduce new import controls on EU meals merchandise this summer season, however their arrival has been postponed for a fourth time. In the event that they ever materialise, importing European merchandise will probably be much more problematic.

4

What’s occurred to different companies

On the finish of June, the EU printed figures exhibiting that between 2020 and 2021, British exports to the remainder of Europe had fallen by 14%. Covid was a part of what had occurred – however, as one high-ranking European commissioner mentioned, the plunge was additionally all the way down to “paperwork for nearly each product delivery between our markets”, and checks on “1000’s of products being carried out every day” – in addition to a sudden mess of VAT, import duties and raised expenses for transporting items from Britain to the continent.

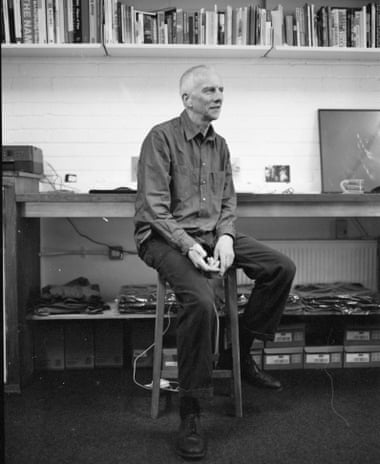

Since 1995, Kenneth Mackenzie has run a high-end males’s casualwear enterprise known as 6876, based mostly in London. Pre-Brexit, he might rely on a resident of Berlin or Paris shopping for his garments on precisely the identical foundation as somebody within the UK. However, since Britain left the EU, he has misplaced someplace between 60% and 70% of his European clients, which accounts for about 30% of his enterprise. “They simply don’t need the effort,” he says. “They don’t need to pay the responsibility and the VAT.”

Worse nonetheless, he now has to hack his approach by means of a tangle of complexity that surrounds the clothes factories he makes use of on the continent, who cost far lower than producers in Britain, and thereby make his enterprise viable. He makes use of an organization in Portugal to fabricate his jackets, to exacting specs. However now, due to customs checks and byzantine courier preparations, he’s by no means positive how lengthy it can take for completed merchandise to reach again within the UK. “You may pay for a two-day service, getting issues again, and it’ll take 9 days now,” he says. “It’s insane; it’s really bought slower. Earlier than Brexit, you can get stuff in two days, and even in a single day, when you paid for it. Now, it simply comes when it comes. Packing containers get break up: I’ll be checking on the web pondering, ‘Why’s this field in France? Why’s that one within the UK?’”

5

Queues that even British individuals can’t deal with

It was simply probably the most vivid illustration to date of how Brexit has upturned issues that hundreds of thousands of Britons as soon as took as a right: the episode that exploded into the information on Friday 22 July, when the Port of Dover declared a “important incident”, as droves of individuals making an attempt to get to the continent had been stranded in six-hour queues.

Even Jacob Rees-Mogg was compelled to confess this week that he was wrong to say Brexit would not cause delays at Dover. The port’s chief govt – together with an array of Conservative politicians – blamed inadequate staffing at French border posts, however there was an apparent associated situation: the plain indisputable fact that British travellers now need to undergo the bureaucratic ritual of getting their passports stamped, as an alternative of going by means of the pre-Brexit quickfire checks (the everyday processing time has reportedly gone from 58 to 90 seconds – which, once you’re coping with 1000’s of individuals, is clearly an enormous soar). A lot the identical applies to the multitudes of British people who find themselves now arriving in Spain – the place, at airports in Mallorca, Ibiza and Alicante, there have been stories of lengthy queues for the “third nation” entry factors that they need to now use. Worse nonetheless, Spanish border employees could now ask for proof of a return airplane ticket, the place British arrivals are staying, and ensures that they will spend at least £85 a day. The Austrian every day newspaper Kleine Zeitung lately summarised all these tales, saying, with no schadenfreude in anyway: “The British self-discipline of queueing is sometimes put to the take a look at at EU airports. It’s a consequence of Brexit that leaves a nasty style in a number of the kingdom’s vacationers.”

Nearly each main financial system on the planet is going through massive issues, and the nations of mainland Europe aren’t any exception. However whereas the EU’s gross home product (GDP) per head has grown by 8.5% since Brexit, the UK’s determine is simply 3.8%. Furthermore, the UK is now behind all the opposite G7 nations in its restoration from the pandemic. If a rustic shrinks its export markets, strangles its provide routes and creates labour shortages, that is what occurs – a view backed up by the federal government’s personal forecaster, the Workplace for Finances Duty (OBR). Its basic prediction stays in keeping with what it projected in March 2020: that Brexit would cut back UK productiveness and GDP by 4% in contrast with remaining within the EU. The OBR says that a bit over half of that injury has but to hit us.

There’s a piquant twist to the a part of the post-Brexit story. In June this yr, the Workplace for Nationwide Statistics revealed that within the July-September quarter of 2021, England and Scotland’s GDP had grown by 0.6% and 0.9% respectively, and Wales’s had barely shrunk. Due to the controversial Northern Eire protocol, against this, that a part of the UK was nonetheless benefiting from buying and selling within the EU single market, and its GDP had gone up by 1.4%.

The UK has the best inflation price of any nation within the G7: larger than France, Italy and Germany. To state the apparent, the conflict in Ukraine and pandemic-related provide points are sending costs hovering internationally, however what provides Britain a very pronounced downside – which forecasters say will endure into the quick future, whereas inflation within the eurozone begins to fall – is Brexit. Our departure from the EU has weakened the pound, which will increase the costs of imports, and provides to firms’ prices. Submit-Brexit limitations on international employees are additionally hitting agency’s backside traces, as are issues with the UK’s European provide chains. In April, Adam Posen, an American economist and former member of the Financial institution of England’s financial coverage committee, mentioned that 80% of the reason for Britain’s larger inflation was sure up with Brexit and its limitless complexity. It amounted, he mentioned, to “a commerce conflict the UK declared on itself”.

The federal government has tried to patch up not less than a number of the injury Brexit has inevitably precipitated to British universities and analysis. There’s one apparent instance: rather than the UK’s participation within the EU’s Erasmus+ programme – which, pre-Brexit, allowed 1000’s of UK college students to review or prepare in Europe, and folks from EU nations to do the identical right here – there’s now the Turing scheme, which can present funding for about 40,000 British college students a yr to review and work overseas.

However Brexit has drastically modified the UK’s universities, what they do, and the individuals who work and research in them. Between 2020 and 2021, there was a 40% drop within the variety of college students from EU nations coming to the UK. Teachers say that their European colleagues are more and more reluctant to work right here – partly as a result of instructing and analysis typically will depend on individuals being cell sufficient to maneuver from one establishment to a different, typically with their households, and Brexit has put no finish of limitations in the best way.

One latest story crystallises what is occurring. As Britain left the EU, UK negotiators managed to safe affiliate membership of Horizon Europe, the EU’s €95.5bn (£80bn), seven-year “framework programme for analysis and innovation”. However in July, it was introduced that due to the federal government’s failure to resolve points round Brexit and Northern Eire, 115 of its grants for UK-based analysis initiatives had been being cancelled. British involvement in Horizon Europe is now significantly doubtful: the UK authorities says it has a backup funding plan for researchers, however there’s widespread suspicion that it is going to be an inferior, inward-looking model of a programme that introduced British universities no finish of advantages.

Thiemo Fetzer is a 36-year-old, German-born professor of economics on the College of Warwick. The Horizon announcement threatened the cancellation of a €1.5m analysis venture he had been making ready for a yr, which can look – amongst different issues – at how the media internationally covers the local weather disaster, and its political implications. He has now transferred the venture to the College of Bonn in Germany, the place he’ll quickly spend 50% of his time. “It’s been extraordinarily unsettling, very tough to cope with emotionally,” he says. “I contemplate the UK my residence, however it’s a house that retains on rejecting me. I hope to start out a household within the subsequent couple of years, and I don’t know whether or not the UK’s place to try this.”

Some individuals who make their dwelling from fishing had been amongst Brexit’s loudest supporters, inspired to stay up for a brand new ocean-going utopia of unrivalled entry to British waters, and the binning of European guidelines and laws. When Boris Johnson’s deal with the EU was introduced, these hopes palpably light, although there have been some who tried to hold on to a bit optimism: within the view of the commerce journal Fishing Information, the settlement not less than secured “tariff- and quota-free exports to the EU, though with a massively elevated burden of paperwork”.

The latter entails a complete new world of ache. Jamie McMillan – who didn’t vote within the 2016 referendum in any respect, one thing he says he regrets – runs Lochfyne Langoustines, a small seafood enterprise on the shores of the ocean loch in west Scotland from which it takes its title. The corporate sells “stay langoustines, stay king scallops, stay lobster, stay razor clams – premium merchandise that may obtain very excessive costs”.

Once we communicate, it doesn’t take lengthy for him to get all the way down to the fundamentals of his place. “We now not export to Europe,” he says. “We’ve misplaced 60% of our turnover. We tried to do it, however 4 months after Brexit, we realised it was now not viable. We’re a small firm, and after Brexit, it price us £500 per day per dispatch. It’s barely value it.” His elevated prices, he explains, are all the way down to customs declarations, new expenses, well being certificates that now need to be accomplished for each number of shellfish, and extra. “Within the first 4 months of 2020, we needed to spend £17,500 simply on paperwork. We are able to’t afford that.”

Earlier than Brexit, Lochfyne Langoustines employed 23 individuals. That quantity is now 13. The corporate is now making an attempt to draw enterprise in Singapore, Hong Kong, the US and elsewhere – one thing McMillan says exhibits promising indicators, however will take years to essentially mattress in. Buying and selling with such nations, furthermore, entails spurning markets on his doorstep in favour of flying shellfish midway all over the world. “It’s absolute insanity. However it’s simpler and faster for me to promote merchandise to China than it’s to France.”

10

The humanities – and music specifically

For musicians, actors and the multitudes of individuals whose work places them on stage, Brexit quantities to a very mind-boggling tangle of guidelines, calls for and costs that merely didn’t exist when practitioners of the humanities might work and journey freely round mainland Europe. Clearly, this cuts each methods: fewer European performers fancy coming right here, and proficient individuals within the UK have to seek out methods of surmounting limitless obstacles, if they will. The outcomes of the latter downside are apparent: figures lately printed by the marketing campaign group Finest for Britain present that the variety of British musicians taking part in at EU festivals this summer season has fallen by 45% in contrast with the interval instantly earlier than Brexit and the pandemic.

Sarah McQuaid is a folks musician based mostly in Cornwall. She excursions on probably the most stripped-down foundation conceivable: in a single automotive, together with her manager-cum-roadie. She tends to play very intimate venues – in Berlin, she tells me, her favorite place has a capability of 60 – however between tickets and on-the-road gross sales of vinyl LPs, CDs, T-shirts and different “merch”, that mannequin has at all times allowed her to simply about make a dwelling.

Brexit has upturned every little thing. “Continental Europe was the one place I might get good audiences, and actually good merch gross sales,” she says. “Even with the price of ferries getting over there, I might nonetheless earn extra in 4 weeks than I’d make in twice that period of time within the UK. You might earn as little as €400 on a price, however make the identical quantity on merch gross sales. So, for a solo artist like me, it labored.”

She says she is aware of musicians who’ve now merely determined to cease taking part in in Europe. One downside is the totally different VAT regimes in every European nation: “I’m presupposed to register for VAT in each single one among them, declare the worth of all of the merch I’m bringing in to promote, and pay VAT on it. After which after I depart the nation, I can reclaim the VAT, so long as I can present that I’m bringing all of the stuff out once more.” One other situation is import responsibility. After which there are Carnets: the paperwork that now need to element the tools being moved from nation to nation, and that entail sizeable charges (McQuaid’s newest one price £379.25 – for the form of operation surrounding a band or theatre firm, the prices are inevitably much more punishing).

When she lately toured Eire, what struck her probably the most was the spectacle of customs officers having to test her load as she arrived by ferry: “They’re not there to be sure that musicians who take a PA system overseas take it again in once more. They’re there to catch people-smuggling.”

She sighs, after which echoes one thing I’ve heard from nearly everybody I’ve spoken to: a way of guidelines, preparations that make no sense, and are upturning individuals’s lives. “It’s such a waste of everybody’s time,” she says. “Why do it?”